Anxiety, one of the most common underlying causes of challenging student behavior, typically goes undiscovered and unaddressed through school-based behavior supports. Jessica Minahan and Stuart Ablon combine their expertise as a behavior analyst and a psychologist to outline how best to support students whose anxiety leads to challenging behavior. They describe the role of anxiety in challenging behavior and introduce skill-building approaches that help students develop the skills they need to succeed. These approaches can help teachers analyze skill deficits in students with anxiety, identify strategies to prevent anxiety from escalating, and build skills by combining opportunities to practice problem solving with specific strategies to manage anxiety.

By Jessica Minahan, Ph.D., BCBA, J. Stuart Ablon, Ph.D.

This article appears in the May 2022 issue of Kappan, Vol. 103, No. 8, pp. 43-48.

“Take your seat, please!” Ms. Chen calls to Sam, the last student remaining by the microscopes. As he slowly makes his way to his seat, Sam lets out an audible groan when Ms. Chen asks the class to write a journal entry about the science observation they just completed. Several minutes later, the other students are starting to type, but Sam hasn’t opened his Chromebook and is sitting with his head on his desk, flicking the closed computer with his finger, mumbling, “This is stupid. I stink at writing. She saw that we just did it. Why do we have to write about it?” Ms. Chen calls across the room, “Sam, get to work. This assignment is a big part of your grade!” Sam kicks his desk and walks out of the classroom, muttering, “Do it yourself!” Ms. Chen immediately texts the principal, “Sam left again — help!”

Challenging student behavior (like Sam’s) is one of the leading causes of teacher burnout (Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2017). This is no surprise, as new teachers receive almost no training in mental health or behavioral principles, and both teachers and their schools often become stuck in patterns of reacting to student behavior in the moment, rather than learning about the reasons behind students’ challenging behavior and taking steps to prevent it or to address the root causes of it. However, and given the social-emotional challenges students are currently facing (Racine et al., 2021), teachers urgently need preventative, trauma-sensitive strategies to intervene successfully.

Anxiety is one of the most common underlying causes of challenging behavior, yet it typically goes undiscovered and unaddressed through school-based behavior supports. Our experience and the frameworks we use as a psychologist and a behavior analyst have given us insight into the role of anxiety in challenging behavior and how educators can help students with anxiety develop the skills they need to succeed in any setting. By teaching struggling students key skills early on, we set them up for greater lifelong success in managing their anxiety and behavior.

Anxiety, which spiked during the pandemic (Hawes et al., 2021), is the most prevalent of all mental health disabilities (Ghandour et al., 2019). Many youth continue to experience anxiety or other mental health disorders in adulthood (Ginsburg et al., 2014), with students of color at greater risk (Salari et al., 2020). Yet, anxiety is often a hidden disability, remaining invisible until behaviors emerge that look similar to those of students with low frustration tolerance or chronically oppositional profiles (e.g., yelling, crying, leaving the classroom, and shutting down; Nabors, 2020).

Anxiety is one of the most common underlying causes of challenging behavior, yet it typically goes undiscovered and unaddressed through school-based behavior supports.

In schools, the conventional notion has been that students choose to behave poorly in order to attain or avoid something, and so approaches to school discipline tend to revolve around motivating students to curb challenging behavior. However, decades of research show that students who struggle to manage their behavior do not lack the will to behave well, they lack the skills to behave well. Challenging behavior is linked with deficits in areas of neurocognitive skill such as social cognition, attention and working memory, emotion and self-regulation, cognitive flexibility, and executive functioning (Balderston et al., 2020; Pearcey et al., 2021; Robson, Allen, & Howard, 2020; Zainal & Newman, 2021). To help students manage their behavior, interventions should focus less on rewards and consequences and more on building skills.

It’s essential to understand this neuropsychological relationship between anxiety, skills, and behavior to effectively support students with anxiety. Their behavior may appear purposeful when anxiety is actually compromising their ability to control their actions. Students with significant anxiety may possess these skills, but their anxiety interferes with their ability to access them when needed. For these students, behavior intervention plans that rely on traditional approaches, such as sticker charts or point systems, are unlikely to yield long-term change because incentives do not teach skills or help students apply them when their anxiety levels are high. Viewing misbehavior as a symptom of a skill deficit empowers educators to shape effective responses that include both anxiety prevention and skill-building strategies.

We can start to determine which underdeveloped skills are contributing to a particular student’s maladaptive behavior by reviewing psychological testing, classroom observations, and other assessments. The most common underdeveloped skills impaired by anxiety are in the areas of self-regulation, social thinking (perspective-taking), flexible thinking, executive functioning, and accurate thinking (for specific examples of skills in these domains, visit https://buff.ly/3BDa5IY). To spot where students need support, we need to examine the antecedents to their challenging behavior (things that occur right before the behavior) and determine what skills students might need to respond more appropriately to those antecedents. Once we’ve identified the antecedents and underdeveloped skills, we can support students by teaching strategies for managing antecedents and using skill-building techniques.

Let’s return to Sam. What antecedents and underdeveloped skills might be at play? The counselor reports that Sam is quite anxious, with a history of avoiding work, particularly writing activities. She also explains that he can be triggered when corrected on his behavior or schoolwork. Recent psychological testing noted anxiety toward schoolwork and weaknesses in executive functioning, self-regulation, flexible thinking, and interpreting other’s intentions (perspective-taking).

We saw these skill deficits in Sam’s behavior in science class. First, the writing assignment and then Ms. Chen’s public correction served as antecedents to Sam’s behavior. He participated in the hands-on portion of the assignment, but, when asked to write, he had a difficult time initiating and expressed his negative thoughts about writing. When Ms. Chen reminded Sam, “This is a big part of your grade,” she unintentionally increased his anxiety and missed an opportunity to view his avoidance of writing as a sign of anxiety requiring support. Instead of assuming that Sam was trying to get out of his work, it would likely have been more productive to start from the assumption that Sam would, in fact, prefer to be successful. Then, Ms. Chen might have considered his skills struggles that have made the work hard for him.

Several areas of underdeveloped skills likely contributed to Sam’s poor reaction to the writing assignment:

Using the previous information about some of Sam’s antecedents and the types of skills he may need to strengthen, Ms. Chen can focus on an approach to reducing his anxiety and building his skills.

Recognizing antecedents enables teachers to understand what kinds of classroom situations are likely to trigger students’ anxiety and take steps to limit or defuse those situations. For Sam, this means building a stronger relationship with his teachers and increasing his comfort level in the classroom. Regardless of the specific approach used to build students’ skills at managing anxiety, we must remember that the best predictor of success in helping students develop these skills will be the relationship their teacher is able to foster with them. When students know educators care about them, they feel connected and supported and are better able to accept their guidance as they develop greater resilience and self-esteem.

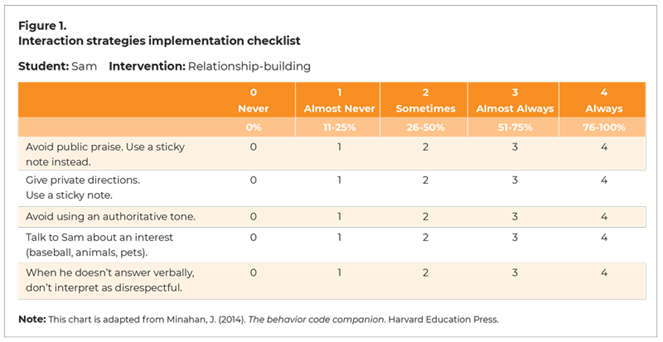

However, creating these connections is not instinctive for all adults. Advising a teacher to “build a relationship” is too vague. Instead, it’s more helpful to create an implementation checklist (see Figure 1) with a bulleted list of specific tips for relationship-building. This may include the student’s interests (e.g., “Sam loves baseball” or “He will easily engage in a conversation about your pet”) and other helpful advice about other ways to be successful with the student (Minahan, 2014). For Sam, this might include a note that public redirection provokes his anxiety. If Ms. Chen had known this, she would not have called to him from across the room. And if she had understood that Sam is uncomfortable with public, authoritative directions and finds them threatening, she might have opted to give him private directions by, for example, writing him a sticky note and quietly delivering it, or typing a private message to him in Google Docs and stepping away quickly to give him space to process it.

Most teachers will find it impossible to avoid every antecedent that might spark a student’s anxiety, so it’s important to help students build skills to manage those feelings as they occur. Collaborative Problem Solving® (CPS) is an evidence-based approach that helps students build skills by using existing behavior problems as opportunities to practice problem solving in relationship with their teachers (Ablon & Pollastri, 2018, Pollastri et al., 2013).

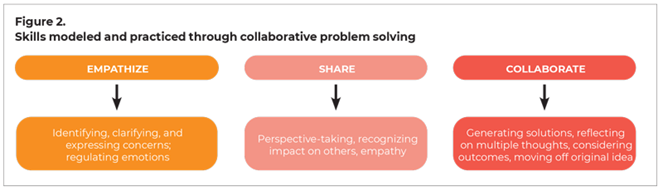

When using CPS, teachers are encouraged to first identify antecedents or triggers with as much specificity as possible and then use them as problems to solve together with the student. In Sam’s case, being asked to write a journal entry about his science observation in class was an antecedent. Having recognized this, Ms. Chen can find a good time to talk with him when he is calm so they can address the issue proactively together. The conversation consists of three ingredients:

To begin with the first ingredient (empathize), Ms. Chen has a private conversation with Sam that is focused on the antecedent (writing journal entries), rather than Sam’s behavior in response (work refusal and disrespectful language). Focusing on the antecedent as a problem to solve together, instead of confronting Sam about his behavior, reduces Sam’s anxiety and helps prevent him from escalating or shutting down. If needed, Ms. Chen reassures Sam that he isn’t in trouble while explaining that she simply wants to understand what was going on for him when she asked him to complete the journal entry. She then goes into detective mode by asking questions and making educated guesses, if needed, to try to clarify his perspective on the issue and understand what was hard for him. Ms. Chen then reflects back whatever information she gleans from Sam to make sure she understands his perspective. Through this process of empathic exploration, she learns that Sam has all the ideas in his head but that he can’t seem to get them out onto paper. Once she understands what is hard for Sam about the assignment, and if Sam seems calm, she can move to the second ingredient.

Having clarified Sam’s perspective, Ms. Chen then proceeds to the second ingredient and shares her concern about the problem they’re trying to solve together. In this case, she shares that being able to document your observations is an important skill in science and what she uses to assess if students are learning the material. Note that Ms. Chen should only share her concern about the problem, not any potential solutions to the problem.

Now that she’s identified both sets of concerns (Sam’s and hers), Ms. Chen moves to the last ingredient (collaborate) and invites Sam to brainstorm any potential solutions that would work for both of them. It is important to always give the student the first chance to suggest a solution because it represents an additional assessment opportunity, provides skills practice, and generates buy-in. If Sam is unable to generate any ideas, she could tentatively suggest one. Regardless of whose idea it was, Ms. Chen would encourage Sam to test out any potential idea with her using a simple litmus test of whether the solution 1) is mutually satisfactory (addresses both parties’ concerns); 2) is realistic and doable; and 3) doesn’t create any new problems. Sam suggests that he just tell her his observations verbally, but this doesn’t pass the litmus test because it’s not realistic for Ms. Chen. But his suggestion does spark the idea that he could get his thoughts on paper by speaking his observations using the speech recognition software they use sometimes in class. Now that they have at a solution that satisfies the litmus test, Ms. Chen and Sam agree to try it and then check back in to see how it worked.

The CPS process is not only aimed at solving the problem to reduce Sam’s challenging behavior, it also builds the relationship between Sam and his teacher while he learns and practices a variety of skills that students with anxiety sometimes need help with (see Figure 2). The fact that students practice these skills naturally through the problem-solving process has multiple benefits, including

It’s unlikely that the first attempt at this process will arrive at a durable solution, but repeated attempts serve as the practice required to learn these problem-solving skills.

The CPS approach helps students build skills through naturalistic opportunities to problem solve. When this approach is combined with more prescriptive lessons in skill-building, it can be even more effective. In Sam’s case, we know he is struggling with accurate thinking, self-regulation, and executive functioning. Now that Ms. Chen has some strategies in place to manage some of the antecedents that elicit challenging behavior, she can consider how to augment these strategies with explicit teaching of the skills Sam needs.

Sam’s statement that he “stinks at writing” shows his inaccurate thinking at work. We often try to reassure these students, telling them, “No, you are a great writer!” But reassurance doesn’t change inaccurate thinking, and it is more effective to disprove students’ inaccurate thinking by showing proof to the contrary (Minahan, 2014).

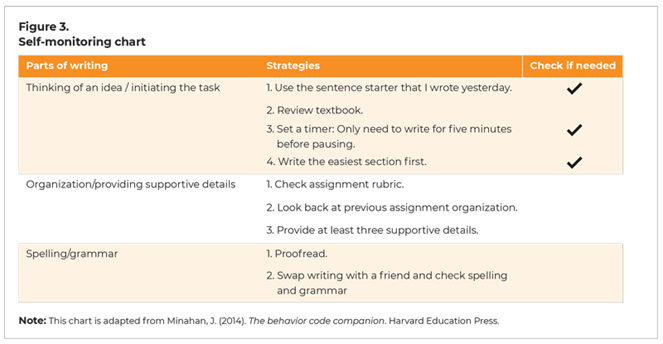

If, for example, Sam were to write an essay, Ms. Chen could ask him privately to self-monitor his work using a three-column chart that includes a column listing various parts of the writing process to be completed (e.g., initiating the idea, providing supportive details, spelling) and a middle column listing strategies that might help if he struggles with any of these steps (e.g., look back at a previously written paper to see how it’s organized). When Sam finishes writing his essay, Ms. Chen could ask him to look at his chart and put check marks in the final column next to the strategies he actually needed to use (see Figure 3). It is likely that Sam will only check strategies for initiating the writing, and Ms. Chen can point out that most parts of the writing project went smoothly. Over time, Sam will understand that getting started with writing is the only difficultly for him and will eventually replace inaccurate thoughts (“I stink at writing”) with more surmountable challenges (“I often have trouble initiating the idea”).

Self-Regulation Skills: Distraction

It’s common knowledge that students benefit from taking breaks from their work. The goal of any break is to help the student be more regulated and calmer when it is over. So it might seem natural to suggest that students like Sam step away from their assignment to calm their nerves when they’re struggling. However, this result can be more difficult to achieve with anxious students. For students with anxiety (like Sam), the problem is anxious thinking about the assignment, not the assignment itself. Movement and sensory breaks would allow Sam time to ruminate in negative thoughts, and he could actually become more anxious as a result.

When we can’t sleep at night, many adults have learned to read a book or watch TV. The input from a book or TV show can distract us from the anxiety-provoking thoughts and allow us to regain enough regulation to sleep. This type of cognitive distraction is key to emotional regulation, and it can be used with students (Minahan, 2014). Instead of taking a movement break, Sam could learn to use cognitive distraction breaks before a writing activity, such as reading a comic, answering trivia questions, or counting all the green items in the room. Silencing the source of his anxiety and achieving calm in this way will allow him to engage in the task in a regulated state.

Executive Functioning Skills: Thinking Ahead

When we are anxious, the executive function skills that keep us on track often falter. Once Sam’s anxiety has set in and his executive skills have plummeted, helping him initiate and organize his thoughts is an uphill battle. For that reason, it will be helpful to prepare some tools for organizing anxiety-provoking assignments and teach Sam to use them in advance.

Sentence starters, for example, are a tried-and-true strategy for open-ended assignments, but they need to be tweaked to be effective for Sam. Because Ms. Chen knows that Sam gets overwhelmed when given a writing assignment, she can support Sam to initiate sentences in his journal long before he is anxious about it. For example, the day prior to the experiments, Ms. Chen could have Sam write in his journal, “The greatest challenge we faced in the experiment was _____ .” This could prevent Sam from focusing on the whole assignment (“I have to write three pages”) and experiencing an avalanche of overwhelming thoughts. Now, in the moment, Sam will bypass anxious thoughts with an accurate thought: “I only have to finish the sentence.” (Minahan, Ward, & Jacobsen, 2021). Even though Sam was anxious about the idea of writing in science class, the actual task of finishing the last few words of the question might seem doable.

At first glance, Sam’s behavior in the science classroom felt willful and combative. However, his behavior stemmed not from a desire to avoid work but from a desire to do his work well. When we educate ourselves on the impact of anxiety and begin to be curious as to why students behave as they do, we build empathy with our students which allows us to address behavior with a collaborative approach. A skill-building approach that focuses on identifying antecedents, solving problems, and learning new strategies can help Sam and other students like him develop the tools they need to learn and thrive in school and beyond.

References

Ablon, J.S. & Pollastri, A.R. (2018). The school discipline fix: Changing behavior using collaborative problem solving. Norton.

Balderston, N.L., Flook, E., Hsiung, A., Liu, J., Thongarong, A., Stahl, S., . . . & Grillon, C. (2020). Patients with anxiety disorders rely on bilateral dlPFC activation during verbal working memory. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 15 (12), 1288-1298.

Ghandour, R.M., Sherman, L.J., Vladutiu, C.J., Ali, M.M., Lynch, S.E., Bitsko, R.H., & Blumberg, S.J. (2019). Prevalence and treatment of depression, anxiety, and conduct problems in U.S. children. The Journal of Pediatrics, 206, 256-267.

Ginsburg, G.S., Becker, E.M., Keeton, C.P., Sakolsky, D., Piacentini, J., Albano, A.M., . . . & Kendall, P.C. (2014). Naturalistic follow-up of youths treated for pediatric anxiety disorders. JAMA Psychiatry, 71 (3), 310-318.

Hawes, M., Szenczy, A., Klein, D., Hajcak, G., & Nelson, B. (2021). Increases in depression and anxiety symptoms in adolescents and young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic, Psychological Medicine, 1-9.

Minahan, J. (2014). The behavior code companion: Strategies, tools, and interventions for supporting students with anxiety-related or oppositional behaviors. Harvard Education Press.

Minahan, J., Ward, S., & Jacobsen, K. (2021/2022). What can teachers do to engage anxious students? Educational Leadership, 79 (4), 64-70.

Nabors, L. (2020). Conduct problems and anxiety in children. In Anxiety management in children with mental and physical health problems (pp. 117-133). Springer.

Pearcey, S., Gordon, K., Chakrabarti, B., Dodd, H., Halldorsson, B., & Creswell, C. (2021). Research review: The relationship between social anxiety and social cognition in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 62 (7), 805-821.

Pollastri, A.R., Epstein, L.D., Heath, G.H., & Ablon, J.S. (2013). The collaborative problem solving approach: Outcomes across settings. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 21 (4), 188-199.

Racine, N., McArthur, B.A., Cooke, J.E., Eirich, R., Zhu, J., & Madigan, S. (2021). Global prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents during COVID-19: A meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatrics.

Robson, D.A., Allen, M.S., & Howard, S.J. (2020). Self-regulation in childhood as a predictor of future outcomes: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 146 (4), 324-354.

Salari, N., Hosseinian-Far, A., Jalali, R., Vaisi-Raygani, A., Rasoulpoor, S., Mohammadi, M., . . . & Khaledi-Paveh, B. (2020). Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Globalization and Health, 16 (1), 1-11.

Skaalvik, E.M. & Skaalvik, S. (2017). Dimensions of teacher burnout: Relations with potential stressors at school. Social Psychology of Education, 20 (4), 775-790.

Zainal, N. & Newman, M. (2021). Within-person increase in pathological worry predicts future depletion of unique executive functioning domains. Psychological Medicine, 51 (10), 1676-1686.

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| __cf_bm | 1 hour | This cookie, set by Cloudflare, is used to support Cloudflare Bot Management. |

| __hssc | 1 hour | HubSpot sets this cookie to keep track of sessions and to determine if HubSpot should increment the session number and timestamps in the __hstc cookie. |

| __hssrc | session | This cookie is set by Hubspot whenever it changes the session cookie. The __hssrc cookie set to 1 indicates that the user has restarted the browser, and if the cookie does not exist, it is assumed to be a new session. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-advertisement | 1 year | Set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin, this cookie records the user consent for the cookies in the "Advertisement" category. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| CookieLawInfoConsent | 1 year | CookieYes sets this cookie to record the default button state of the corresponding category and the status of CCPA. It works only in coordination with the primary cookie. |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| li_gc | 6 months | Linkedin set this cookie for storing visitor's consent regarding using cookies for non-essential purposes. |

| lidc | 1 day | LinkedIn sets the lidc cookie to facilitate data center selection. |

| UserMatchHistory | 1 month | LinkedIn sets this cookie for LinkedIn Ads ID syncing. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| __hstc | 6 months | Hubspot set this main cookie for tracking visitors. It contains the domain, initial timestamp (first visit), last timestamp (last visit), current timestamp (this visit), and session number (increments for each subsequent session). |

| _ga | 1 year 1 month 4 days | Google Analytics sets this cookie to calculate visitor, session and campaign data and track site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookie stores information anonymously and assigns a randomly generated number to recognise unique visitors. |

| _ga_* | 1 year 1 month 4 days | Google Analytics sets this cookie to store and count page views. |

| _gat_gtag_UA_* | 1 minute | Google Analytics sets this cookie to store a unique user ID. |

| _gid | 1 day | Google Analytics sets this cookie to store information on how visitors use a website while also creating an analytics report of the website's performance. Some of the collected data includes the number of visitors, their source, and the pages they visit anonymously. |

| AnalyticsSyncHistory | 1 month | Linkedin set this cookie to store information about the time a sync took place with the lms_analytics cookie. |

| CONSENT | 2 years | YouTube sets this cookie via embedded YouTube videos and registers anonymous statistical data. |

| hubspotutk | 6 months | HubSpot sets this cookie to keep track of the visitors to the website. This cookie is passed to HubSpot on form submission and used when deduplicating contacts. |

| vuid | 1 year 1 month 4 days | Vimeo installs this cookie to collect tracking information by setting a unique ID to embed videos on the website. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| bcookie | 1 year | LinkedIn sets this cookie from LinkedIn share buttons and ad tags to recognize browser IDs. |

| bscookie | 1 year | LinkedIn sets this cookie to store performed actions on the website. |

| li_sugr | 3 months | LinkedIn sets this cookie to collect user behaviour data to optimise the website and make advertisements on the website more relevant. |

| NID | 6 months | Google sets the cookie for advertising purposes; to limit the number of times the user sees an ad, to unwanted mute ads, and to measure the effectiveness of ads. |

| test_cookie | 15 minutes | doubleclick.net sets this cookie to determine if the user's browser supports cookies. |

| VISITOR_INFO1_LIVE | 6 months | YouTube sets this cookie to measure bandwidth, determining whether the user gets the new or old player interface. |

| YSC | session | Youtube sets this cookie to track the views of embedded videos on Youtube pages. |

| yt-remote-connected-devices | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the user's video preferences using embedded YouTube videos. |

| yt-remote-device-id | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the user's video preferences using embedded YouTube videos. |

| yt.innertube::nextId | never | YouTube sets this cookie to register a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

| yt.innertube::requests | never | YouTube sets this cookie to register a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| __Secure-YEC | 1 year 1 month | Description is currently not available. |

| _cfuvid | session | Description is currently not available. |

| _pk_id.d014234b-506e-4c9f-8f74-9ecfcde5874f.838e | 1 hour | Description is currently not available. |

| _pk_ses.d014234b-506e-4c9f-8f74-9ecfcde5874f.838e | 1 hour | Description is currently not available. |

| cf_clearance | 1 year | Description is currently not available. |

| ppms_privacy_d014234b-506e-4c9f-8f74-9ecfcde5874f | 1 year | Description is currently not available. |

| VISITOR_PRIVACY_METADATA | 6 months | Description is currently not available. |